Abstracts

Abstract

Expertise as an indicator of a translator’s competence has experienced a growing amount of research interest recently, but little attention has been paid to the role of registerial expertise, especially in medical translation. This study aims to carry out a systemic functional investigation of the role that a translator’s registerial expertise plays, namely medical expertise, in the translations of Huang Di Nei Jing, the most ancient and important medical classic in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The focus is on the logical choices made by both clinician and non-clinician translators. The findings report a few interesting patterns in the translators’ logical choices in relation to their medical expertise. Firstly, clinician translators tend to have a higher degree of intervention through their strategic logical choices, and their translations tend to be more grammatically intricate. They are also found to have a stronger sense of the logical relationships in modelling medical events according to their importance. Further, although mother tongue is found to be impactful on the translators’ logical choices to some degree, it is the registerial expertise that has been found to play the major role. The evidence reported in this study suggests that the translator’s registerial expertise should be included as an important component of translator training.

Keywords:

- registerial expertise,

- logical choice,

- medical translation,

- systemic functional linguistics (SFL),

- Huang Di Nei Jing

Résumé

L’expertise, en tant qu’indicateur de la compétence traductionnelle, a récemment fait l’objet d’un intérêt croissant de la part des chercheurs, toutefois ils n’ont guère prêté attention au rôle de l’expertise scientifique, en particulier en traduction médicale. La présente étude est une recherche fonctionnelle systémique du rôle de l’expertise scientifique, expertise médicale, dans les traductions de Huang Di Nei Jing, le plus ancien et le plus important classique de la médecine traditionnelle chinoise (MTC). Elle se fonde sur les choix logiques effectués par des traducteurs cliniciens et non-cliniciens, et conclut sur quelques modèles intéressants des relations entre les choix logiques des traducteurs et leur expertise médicale. Tout d’abord, les traducteurs cliniciens, par leur choix logiques et stratégiques, tendent à intervenir davantage et leurs traductions sont grammaticalement plus complexes. Ils manifestant aussi un sens plus aigu des relations logiques en relatant les événements médicaux selon leur importance. Ensuite, bien que la langue maternelle exerce une influence considérable sur les choix logiques des traducteurs, c’est l’expérience scientifique qui a le plus d’impact. Les résultats de la présente étude suggèrent que l’expertise scientifique devrait constituer une composante majeure de la formation des traducteurs.

Mots-clés :

- expertise scientifique,

- choix logique,

- traduction médicale,

- linguistique fonctionnelle systémique (LFS),

- Huang Di Nei Jing

Resumen

La experticia, como indicador de la competencia, es objeto de un interés creciente por parte de los investigadores, sin embargo, no se ha prestado la debida atención al papel de la experticia científica, en particular en la traducción médica. El presente estudio apunta a una investigación sistémica funcional del papel de la experticia científica médica en la traducción de Huang Di Nei Jing, el clásico más antiguo y más importante de la medicina tradicional china (MTC). Pone el énfasis en las elecciones lógicas que hacen los traductores clínicos y los no clínicos. El estudio revela algunos modelos interesantes de las relaciones entre las elecciones lógicas de los traductores y su experticia médica. En primer lugar, con sus elecciones lógicas estratégicas, los traductores clínicos tienden a mayores intervenciones y sus traducciones son gramaticalmente más complejas. Además, manifiestan un sentido más agudo de las relaciones lógicas al presentar los acontecimientos médicos según su importancia. Luego, aunque la lengua maternal suele ejercer una gran influencia en las elecciones lógicas de los traductores, es la experticia científica la que tiene el mayor impacto. Los resultados del estudio sugieren que la experticia científica debería ser un componente importante de la formación de los traductores.

Palabras clave:

- experticia científica,

- elección lógica,

- traducción médica,

- lingüística sistémica functional (LSF),

- Huang Di Nei Jing

Article body

1. Introduction

In recent years, the translation market has seen a considerable transformation and an increasing complexity in terms of the demands on translators. This dramatic change has brought forth the expansion of translator training to meet the pressing need of professional translators. The topic of a translator’s expertise has thus attracted a growing amount of research interest from cognitive translatology (Eszenyi 2016). However, the idea of expertise has often been narrowly conceived as bilingual capacity and translation training experience (En and En 2019), leaving the registerial aspect of expertise downplayed and under-researched, something which is in fact crucial in translating highly specialized texts (Goźdź-Roszkowski 2016). The present study sets out to fill this gap and will carry out a systematic investigation of the role that the translator’s registerial expertise plays in the translations of Huang Di Nei Jing, the most ancient and important technical classic in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (Ye and Dong 2017: 11). Departing from previous process-orientated research, this study is product-orientated and will be approached from a new perspective offered by systemic functional linguistics (SFL), a powerful and robust framework ideal for product-oriented research. Two groups of translations by clinicians and non-clinicians, that is, translators with and without medical expertise, will be compared to examine whether and how registerial expertise may make a difference in TCM translation. The central focus is on logical choices, where the role of the translator’s registerial expertise can be maximally investigated through peculiar linguistic features of logical indeterminacy in the conjunction system of classical Chinese.

2. Expertise

Expertise is a key concept with numerous definitions in human resources (Herling 2000). In general, it is usually perceived as a combination of at least three factors: experience, knowledge, and problem-solving skills (Whyatt 2018), which can be gleaned from two major theoretical perspectives: the cognitive perspective, including the individual’s basic information-processing and problem-solving skills, and the perspective of heuristic knowledge, that is, knowledge about a specific domain (Herling 2000). Expertise in translation studies is mostly approached from the cognitive perspective, leaving the domain-specific knowledge part of expertise under-researched.

2.1 Expertise in translation studies

Recently, the expertise of a translator has become an increasingly catchy topic in translation studies. A professional translator, as generally agreed, needs to have varied expertise, for example: bilingual capacity (Amador 2019), internalization of external resources (Whyatt 2012; Redelinghuys and Kruger 2015; Whyatt 2018), intercultural competence (Eszenyi 2016), computational expertise (Rodríguez-Castro 2018; Shreve 2018), deliberate practice (Shreve 2006), or sociological aspects of expertise (Tiselius and Hild 2017). Expertise has different forms, and so a single study usually cannot comment on all aspects of expertise (Shreve 2018). Usually, in translation studies, its definition is limited to the translator’s experiential expertise (En and En 2019), that is, translation training experience and practice. In other words, an expert translator is distinguished from a novice translator by his/her translation experience and translation skills.

Expertise plays a significant role in a translator’s performance and behaviour. For instance, Rojo and Ramos (2018) have offered empirical evidence for the influence of expertise on emotion regulation and its consequences for translation performance. The result suggests that personality factors and expertise level are decisive in regulating emotion and guiding translation behaviour. Many scholars have also investigated expertise in association with translation competence, often raising the question about the relationship between the two, and the variations between translators with different levels of expertise (for example, Pym 2003; Göpferich 2009; Tiselius 2013; Goźdź-Roszkowski 2016; Shreve, Angelone, et al. 2018). Some see expertise and competence as intertwined concepts, with expertise entailing competence, or competence as a prerequisite of expertise (Tiselius 2013; Tiselius and Hild 2017). Others are concerned whether there is a need for the term competence in translation studies given that many widespread and empirically robust frameworks of expertise already exist in cognitive sciences (Shreve, Angelone, et al. 2018).

When it comes to the translation of specialized texts, it is argued that generic competence (that is, the ability to successfully exploit a range of genres to fulfil the goal of a specific professional community) and professional expertise should be included in the range of competence demanded from translators (Goźdź-Roszkowski 2016). As for the differences between professional and non-professional translators, they are often assumed to be self-evident, with the latter seen as less competent in producing a good translation; this has been confirmed bby several studies. For instance, Amador (2019) has found that amateur translators are less effective in their translation tasks. Olalla-Soler (2018)[1] has also discovered that professional translators apply internalized source-culture knowledge more efficiently; therefore, they are more capable of solving cultural translation problems. However, a different voice is heard from other scholars who have worked to develop a more nuanced perspective on translation tasks by non-professional translators. They argue that translations by non-professionals may not necessarily be deficient, sometime even superior in some aspects (Antonini and Bucaria 2016; Baker 2009, 2013; En and En 2019; Khoshsaligheh and Ameri 2017; Tesseur 2017). These seemingly contradictory voices signal a need to enlarge our understanding of expertise, which is why registerial expertise is the focus of the present study.

2.2 Registerial expertise

Registerial expertise, by and large, refers to what has been traditionally called a translator’s domain-specific knowledge (Goźdź-Roszkowski 2016; McCarthy and Goldman 2019) or subject-matter expertise (Holt-Reynolds 1999). Following the concept of register in Steiner (1998), Matthiessen (2009), and Matthiessen, Wang, et al. (2018), the present study re-terms this as registerial expertise: the translator’s domain-specific knowledge, developed as a repertoire of personalized meaning potentials through registerial progression, including the activities of a particular field, the social interactions in that field, and the mode of meaning-conveying.

Registerial expertise is an essential layer of expertise (Herling 2000; Shreve 2018), sometimes playing an even more important role in distinguishing a novice from an expert (Popovic 2004; Shreve 2018). A higher level of domain-specific knowledge will usually empower a writer to have a higher degree of epistemic authority in uttering his/her own voice in a text (Heritage and Raymond 2005; Stivers 2005; Stivers, Mondada, et al. 2011). It is also argued that the better you know a specific domain, the better you are able to know the subject at hand (Shreve 2018). Interestingly, Shreve and Lacruz (2017) found that a translator with extensive knowledge of the domain represented in a text is able to build a richer propositional network, thus producing more accurate meaning-inferencing in text representation. Important as it is, registerial expertise is mostly discussed at the theoretical level, leaving a desperate need for empirical findings to sustain its exploration within translation competence and translator training. This study offers such empirical insights on the role of the translator’s registerial expertise, specifically medical expertise, including his/her clinical experience and medical knowledge. It is a product-based investigation, using translations as end-products; these are the textual evidence of the translator’s semantic choices. Such an investigation, by nature, is an examination through textual analysis of the translator’s subjective interventions.

The focal point will be given to the translators’ logical choices in the translations of the most ancient classic of Chinese medicine, Huang Di Nei Jing. The reason for this choice lies in the unique linguistic features of logical vagueness/indeterminacy in classical Chinese, a peculiar burden in the communication between Chinese medicine and Western medicine (Maciocia 1989/2015). Moreover, logical indeterminacy allows to examine the translator’s subjective interventions: when a text is certain and determinate, the space left for the translator’s interpretation will be small, as s/he is constrained by the source text. Then, the variations between translators’ choices tend to be minimal. However, when a translator is dealing with a highly indeterminate and uncertain text (for example, TCM texts written 2000 years ago, where the contextual distance is so great that a univocal meaning is almost unreachable), the translator’s personal intervention can then be maximally revealed. Indeed, such a text provides more room for the translator to exercise his/her subjectivity. Naturally, the role of a translator’s expertise in his/her translation choices can then be maximally examined and thus the purpose of this article is better served.

3. Logical choice

Language is an evolving socio-semiotic system where meanings, the essentials of translation (House 2001), are construed through experience (Halliday and Matthiessen 1999: 1). Usually, the construction of human experience is thought of as knowledge. However, from a systemic functional perspective, experience is not treated as knowing, but as meaning construed through “systemic patterns of choice” (Halliday and Matthiessen 1999: 1; Halliday and Matthiessen 1985/2014: 23). The present study takes a functional perspective, viewing a translator’s medical expertise (clinical experience and medical knowledge) as their personal meaning potentials aggregated from the medical field. It further regards language as a meaning-making resource at the translator’s disposal to re-construe three basic meta-functions (meanings) simultaneously through translation. The three metafunctions are: 1) ideational, including experiential (where human experiences are construed) and logical meaning (where human experience is construed into a logical sequence); 2) interpersonal (where personal and social relationships are enacted); and 3) textual (where ideational and interpersonal meanings are organized in a cohesive and intelligible way) (Halliday and Matthiessen 1985/2014).

3.1. Logical indeterminacy

Studied within semantics, indeterminacy, or vagueness (Zhang 2015), is an intrinsic feature of natural language (Russell 1923; Weatherson 2010). It occurs when meanings are “continuous” or “fused” with many hypothetical options (Halliday and Matthiessen 1999: 548). As an intricate linguistic phenomenon, its metalinguistic categories are often indeterminate as well (Halliday 2009; Zhang 2015), depending on which perspective is adopted to approach the meaning of language (for example, formal, semantic, pragmatic). Indeterminacy occurs when there is a fuzziness in semantic categorization and it can be caused by various factors, be they epistemic, metaphysical, pragmatic or grammatical (Kies 1990; Trueswell, Tanenhaus, et al. 1994; Santos 1998; Williamson 2003; Niederdeppe 2005; Spranger and Loetzsch 2011; Zhang 2015).[2] The present study approaches the meaning of language from a SFL perspective, more specifically, logical meaning, but the term indeterminacy needs to be understood from the tension of the unique logical system between classical Chinese and English in the process of translating.

Unlike English, classical Chinese is a concise language that does not provide many logical resources. Also, ancient Chinese texts originally had no punctuation nor delimiter that marks the end of the word or sentence (Huang, Sun, et al. 2010; Xu, Wang, et al. 2019). As a result, the linearity of syntactic relationships needs to be worked out by subsequent modern Chinese scholars through judou, that is, sentence segmentation (Jia 2009; Xu, Wang, et al. 2019), which often provokes controversies and indeterminacy. The lack of lexico-grammatical logical resources and the unique grammatical uncertainty in the classical Chinese system (Jiang 2010), together with contextual distance between ancient and modern China, between the East and West, present a near insurmountable challenge for the translator, causing indeterminacy in his/her decision-making. As Veith, a well-recognized translator of Huang Di Nei Jing, points out:

Classical Chinese constantly presents a great many problems. Punctuation is completely unknown and there is no indication whatsoever as to where one sentence ends and the next one begins, and the same Chinese sentence admits many grammatically different interpretations.

Veith 1966: xii-xiii[3]

Needless to say, translating such technical but indeterminate texts is highly consequential since the translator is constructing medical knowledge. The indecision or inconsistency caused by translation may eventually become an issue of life or death in clinical practice (Luo 2005; Matthiessen 2017[4]).

Logical indeterminacy is inherent to classical Chinese’s writing system, the understanding of which is context-dependent but most often unsolvable. As previously discussed, this means that investigating logical indeterminacy in that language is the best way to showcase the translator’s subjective intervention. Furthermore, in the context of TCM translation, there is a fierce debate regarding who should bear the responsibility of such a translation, with some claiming that only clinicians, that is, translators with medical expertise, should be entitled to do so (Rosenberg 2013).[5] Determining who would be the ideal translator, in my view, seems futile when considering translation as a social activity, since each translation has its unique value and individual traits. This study thus seeks to characterize such individuality by examining the role that the registerial (medical) expertise of the translator plays in his/her logical choice during translation. It will compare two groups of medical translations, one by clinicians and the other by non-clinicians, that is, translators with and without medical expertise. It looks at different translations of Huang Di Nei Jing, the earliest and most important classic that has laid the foundation for TCM theory and practice. Two research questions will be answered to fulfil this purpose:

In terms of logical choice, what are the differences in the translations by clinician and non-clinician translators?

How are the differences related to the level of medical expertise?

3.2. The CLAUSE COMPLEX system

The analytical framework in the present study is the logical system of CLAUSE COMPLEX in SFL (Halliday and Matthiessen 1985/2014), as it allows the translators’ logical choices to be investigated in a very dedicated and systematic way (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

CLAUSE COMPLEX system, adapted from Halliday and Matthiessen (1985/2014: 438)

The CLAUSE COMPLEX system firstly has to do with the choices of clauses and clause complexes, which is closely related to the concept of grammatical intricacy quantified by the ratio of the number of clauses to the number of clause complexes in a text (Eggins 1994: 61), an important measurement of text complexity. The higher the ratio of grammatical intricacy, the higher the degree of text complexity is (Halliday 2009). See Example 1 for an illustration:

There are three clauses in the one clause complex, thus the grammatical intricacy is 3. The CLAUSE COMPLEX system is a resource for construing our experience in the world as sequences of “quanta of change,” with each quantum of change being a configuration of a process (Matthiessen 2002: 263). It contains two sub-systems: TAXIS and LOGICO-SEMANTIC TYPE. TAXIS describes the type of interdependency between clauses, known as parataxis and hypotaxis. Paratactic relationships are represented by numbers (1, 2, 3…), indicating that two clauses are potentially independent of one another, each constituting a proposition in its own right. Hypotactic clauses are marked by Greek letters (α, β, γ…), signalling that two clauses are dependent on each other, with the dependent clause being brought in to support the main clause. The interpretation of a clause nexus frequently depends on more delicately differentiated process types.

LOGICO-SEMANTIC TYPE between clauses is first classified into projection (where the secondary clause is projected by the primary clause) and expansion (where the second clause expands on the initial one). Projection relates our experience to a phenomenon of higher order (what people say and think). Expansion relates to a phenomenon as being of the same order of experience and is sub-divided into elaboration (=), extension (+), and enhancement (x). In elaboration, one clause elaborates on the meaning of another by further specifying or describing it. The secondary clause does not introduce a new element, but rather provides further characterization of one that is already there, simply by restating, clarifying, refining or adding a descriptive attribute or comment. In extension, one clause extends the meaning of another by adding something new. What is added may be just an addition (for example, and), a replacement (for example, but) or an alternative (for example, or). In enhancement, one clause enhances the meaning of another by qualifying it in terms of time, place, manner, condition or cause (see Halliday and Matthiessen 1985/2014: 428-548). See Example 2 for an illustration:

Example 2 explains the consequences to the human body if the winter law is violated. It also provides reasons from the ;五;行 [five elements] theory in TCM. Four clauses with 3 nexuses have been identified, two hypotactic and one paratactic. The first clause provides a condition for the second one, which is then enhanced by the next two clauses, providing reasons why the lungs will be hurt. There is no elaborating relationship in this instance.

4. Data and methodology

The data in this study is a selection of four English translations of Hang Di Nei Jing Su Wen, often called Neijing, the earliest classic of TCM compiled by various anonymous authors over an extended period of time (roughly about 200BC to 200AD). Neijing is revered as the Bible within TCM and has laid the foundation for Chinese medicine theory and practice for over two thousand years (Lu 1990).[6] It is well-known for its encyclopaedic coverage of various topics, for example, cosmology, astrology, meteorology, philosophy, physiology, pathology, and acupuncture, each in a separate chapter, forming a unique textus receptus that has been adapted by scholars during different dynasties.

The translations are selected on the basis of the following two criteria:

The translations are based on the same version of the source text, that is, the Chinese version compiled by Wang Bing during the Tang Dynasty, to ensure that they are comparable;

The translations were done by two groups of translators who are differentiated by their medical expertise, that is, translators with and without TCM clinical experience and domain-specific knowledge.

Of the existing 14 English translations, 5 meet these criteria (see Table 1).

Table 1

Overview of the five translations

Table 2

Overview of the five translators

Table 2 presents two groups of translators, with and without medical expertise. As indicated, both Ni and Wu are clinicians with more than 20 years of medical experience; they have received education in the medical field. Conversely, Veith, Unschuld, and Li are non-clinicians and thus have no clinical training or experience. For the purpose of this article, there is a need have minimal differences within each group of translators. Li is thus set aside, as his domain of expertise, linguistics, is very different from that of Unschuld and Veith, who are both medical historians. As a result, the remaining four translations by clinicians (Wu and Ni) and non-clinicians (Veith and Unschuld) were selected for this study.

However, as shown in Table 2, the two groups of translators are not just differentiated by medical expertise, but also by their mother tongue. This means that the different choices made these two groups of translators can be attributed to both medical expertise and mother tongue. There is thus a need to filter out the typological impact of the translator’s mother tongue, as the primary purpose of this article is to investigate the role of medical expertise. To achieve this, Li’s translation was used as a delimiter of the two variables, as Li is both a non-clinician and a native speaker of Chinese; this makes his translation comparable to both groups of translations. When Li’s translation is compared with the translations by clinicians, medical expertise becomes the only variable responsible for potential differences. Likewise, when Li’s translation is compared with those of the non-clinicians, the translator’s mother tongue becomes the only variable. By delimiting one variable from the other, the role of medical expertise can thus be more accurately revealed. In other words, methodologically, the comparison is firstly and primarily done between clinicians (Wu and Ni) and non-clinicians (Veith and Unschuld), and then a further comparison is done between Li and these two groups of translations respectively, serving to further confirm the role actually played by medical expertise.

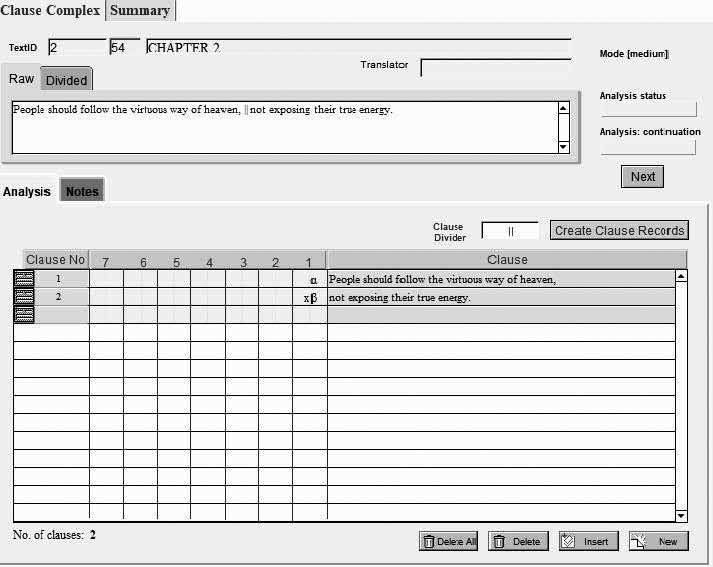

Two chapters of Neijing (chapters 2 and 26, where the problem of logical indeterminacy appears to be the most evident) and their four translations have been selected as the data for this study. A detailed analysis was carried out in the CLAUSE COMPLEX system set up in SysFan (Wu 2000), a database system specifically geared to SFL users for a systemic functional analysis (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

An interface for analyzing clause complexes in SysFan

Altogether, 617 clause complexes and 1753 clauses were analysed and a summary of the translators’ logical choices automatically produced by SysFan (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Summary of the translators’ logical choices by SysFan

5. Findings and interpretation

There are three key findings that show the significant role that medical expertise plays in the translators’ logical choices, namely, the role of medical expertise in grammatical intricacy, tactic, and logico-semantic choices. Each will be elaborated separately in the following subsections.

5.1. The role of expertise in grammatical intricacy

The first finding concerns the role of expertise in the grammatical intricacy of the translations (see Table 3).

Table 3

Grammatical intricacy of the translations by clinicians and non-clinicians

As indicated in Table 3, the average number of clauses per sentence in the translations by Wu and Ni is 2.5 and 2.3 respectively, a higher ratio of grammatical intricacy than in the translations by Unschuld and Veith, with 2.0 and 2.3. This finding suggests that the complexity of a translation tends to vary according to the translators’ expertise: the higher the level of expertise, the higher the degree of complexity of the translation. However, the two sets of data happen to show differences based on another variable, the translators’ mother tongue. This means that the translators’ mother tongue might also play a role in the discrepancy of grammatical intricacy. To further delimit the major contributing factor for this difference, Li’s translation is included as an independent variable for further comparison. As shown in Table 3, the ratio of Li’s grammatical intricacy, 1.9, is closer to the pattern of the translations by Unschuld and Veith. This means that the translator’s mother tongue (the only variable that distinguishes Li from Unschuld and Veith) does not exert any significant impact on grammatical intricacy. This comparison further consolidates the idea that it is the registerial expertise that plays the major role in the grammatical intricacy of a translation.

It also shows that translations by clinicians tend to have a higher degree of intervention in terms of syntactic arrangement. The clause number is either the highest (394 in Wu’s translation) or the lowest (282 in Ni’s translation). On the contrary, translations by non-clinicians tend to see a closer equivalence to the source text, with 361 (Unschuld) and 359 (Veith), respectively, similar to the 357 found in the ST (see Example 3 for illustration):

Example 3 presents the number of clauses both in the source text and the translations. Two clauses are found in Veith’s translation, which is equivalent to the source text; three clauses are found in Unschuld’s translation, that is one more than in the source text. The highest clause number (4) is in Wu’s translation, and the lowest (0) in Ni’s, suggesting a higher degree of intervention compared to the ST.

Syntactic organization is an important area to consider when studying texture, which is traditionally referred to as the “form” and “content” of a text (Hatim and Mason 1990/2014: 192). The translation strategy can be one of free or literal translation (Barbe 1996). This variation, due to translators’ expertise, strongly suggests that expertise makes a difference in the choices of translation strategy: clinicians tend to favour free translation, while non-clinicians tend to favour a literal translation. In other words, non-clinicians tend to be more grammatically constrained by the source text, while clinician translators tend to be freer from the source text grammar. This is demonstrated by Example 4:

4)

逆之|| 则伤肺,|| 冬为飧泻,|| 奉藏者少,||

(No. of clauses: 4)

[Against it will hurt lung, winter will diarrhea, offer store particle few]

Wang ca. 8th c./2015: 7Translations by clinicians:

-

If these principles are violated by a man, || his lung will be hurt, || as lung associates with metal || and the metal prospers in autumn. ||| If one fails to adapt to the property of autumn energy which is harvesting, || one will apt to contract lienteric diarrhea with watery stool containing undigested food in winter. ||| This is because his adaptability to winder energy has been weakened due to his inability of following the property of autumn energy which is harvesting to preserve health. ||| in this case, it is called “inadequate of offering to storing.” |||

(No. of clauses: 8)

-

If this natural order is violated, || damage will occur to the lungs, || resulting in diarrhea with undigested food in winter. ||| [Omitted]

(No. of clauses: 3)

Translations by non-clinicians:

-

Those who disobey the laws of Fall will be punished with an injury of the lungs. ||| For them Winter will bring indigestion and diarrhea; || thus they will have little || to support their storing (of Winter). |||

(No. of clauses: 4)

-

Opposing it harms the lung. ||| In winter this causes outflow of [undigested] food || and there is little || to support storage. |||

(No. of clauses: 4)

One of the key health principles in Chinese medicine is to live a lifestyle according to the atmospheric changes of the four seasons. Example 4 is about the three consequences of disobeying this health principle in the autumn. It shows that non-clinician translators tend to seek out grammatical loyalty to the ST, while clinician translators tend to be more semantically sensitive. As indicated in Example 4, the source text is presented in 4 ranking clauses, which remains the same in the translations by non-clinicians. However, in the translations by clinicians, Wu adds 4 more clauses to make explicit the covert logical meaning, providing the reasons why the lungs will be hurt and why diarrhoea will happen in the winter. Ni also exercises a higher level of intervention, not by adding more clauses, but simply by omitting the translation of the fourth clause of the source text; this suggests a higher degree of intervention.

This variation between translators with and without medical expertise clearly demonstrates that medical expertise is closely related to a translator’s subjective intervention and their strategic choices in organizing their text. Translators with a higher level of medical expertise tend to adopt free translation, adding more information or omitting clauses deemed unimportant. In other words, medical expertise seems to grant more freedom to the translator to intervene in the logical sequence of the source text, as evidenced in Ni’s paratext where he states: “I have taken much liberty in my humble attempt to convey the content of Neijing, such as eliminating … and incorporating them into the main body of translation” (Ni 1995: xv).[7] Conversely, the non-clinician translators give priority to literal translation, which seeks grammatical faithfulness. This suggests that translators without expertise tend to be more grammatically constrained, which is further confirmed by Veith’s paratext, in which he reveals that the syntactical features of the source text served as a close guide to deal with the obscure meanings of the ST.

5.2. The role of expertise in tactic choices

The second finding shows that medical expertise also plays a highly impactful role in translators’ choices regarding taxis (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Tactic and transitivity choices by clinician and non-clinician translators

Figure 4 presents the results of the translators’ tactic choices in relation to their transitivity choices. It shows that clinician translators tend to slightly favour hypotaxis, as indicated by the contrast between the relative percentage of hypotaxis (50.4%) and parataxis (49.6%) in the clinician translations. This tendency becomes more salient when a comparison is done between the ST and the translations, where a sharp increase of hypotaxis, from 6.8% (ST) to 50.4%, and a significant decrease of parataxis, from 93.2% (ST) to 49.6%, are found in clinician translations.

One may argue that the tactic shift from source text to translations can be taken for granted from a typological point of view, given that Chinese is widely acknowledged to be a paratactic language and English, a hypotactic one (Yu 1993; Tse 2010; Bisiada 2013; Liu and Lin 2015). However, tactic choices are more often motivated by pragmatic reasons (Khalil 2011), as indicated by the sharp contrast in tactic choices between clinician and non-clinicians. Indeed, Figure 4 reveals a patterned variation of tactic choices between clinicians and non-clinicians. Unlike with the clinician translations, where hypotactic choices are favoured, the non-clinician translators are found to highly favour parataxis, as suggested by the dominant percentage of 74% (Veith) and 68.9% (Unschuld), respectively. This variation pattern strongly shows that a translator’s medical expertise plays a significant role in their tactic choices.

The interpretation of a clause nexus often depends on more delicately differentiated process types (Matthiessen 2002: 264), which is why tactic choices are better understood when looking at the interaction with translators’ transitivity choices. Figure 4 shows that the logical sequence of events flows differently in the clinician and non-clinician translations, as indicated by the primary choices of processes made by each group of translators. Compared with the translations by non-clinicians, the translations by clinicians see a higher percentage of material process, with 67.9% and 70.4% (clinicians) vs. 59.8% and 59.4% (non-clinicians), and a lower percentage of relational process, with 12.8% and 17.7% (clinicians) vs. 22.9% and 23.8% (non-clinicians). This further suggests that domain expertise makes a difference in terms of how the translators construe experience of Chinese medicine in the translations.

The interaction between translators’ tactic and transitivity choices can be summarized as follows: clinicians tend to build their clinical experience materially and hypotactically. According to Butt and Webster (2017), our world is modelled through the combination of experiential and logical resources. It is often thought that the mainline flow of events tends to be construed paratactically (Thompson 1987). However, this finding shows a counter-expectant pattern, namely that the hypotactic construal of mainline events is possible. This is perhaps partly due to “expectancies,” that is, interactions between the experiential and logical systems (Butt and Webster 2017: 104), and partly to the medical expertise of the translator. Clinician translators are found to have a stronger sense of the relationships between medical activities, as illustrated by their higher tendency to arrange logical relationships hypotactically. See Example 5 for an illustration:

5)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Translations by clinicians:

1 α α

In the morning, he should breathe the fresh air ||

× β

while walking in the yard ||

× β

to exercise his tendons and bones ||

+ 2 α

and loosen his hair||

× β

to make the whole body comfortable along with the generating of spring energy. |||

α

…go walking ||

× β

in order to absorb the fresh, invigorating energy. |||

× β

Since this is the season in which the universal energy begins anew and rejuvenates, ||

α α

one should attempt to correspond to it directly ||

× β

by being open and unsuppressed, both physically and emotionally. |||

Translations by non-clinicians:

1

They should walk briskly around the yard;||

+ 2

they should loosen ||

+ 3

and slow down their movements (body); ||

Move through the courtyard with long strides. ||| |

|

|

|

|

|

Example 5 describes a number of actions that should be taken in order to maintain a healthy lifestyle. The original text is arranged in three paratactic clauses, with three material processes in each translation. The non-clinician translations have strictly followed the ST pattern. However, clinician translations show great differences with the ST, with an increase in both material processes and hypotaxis. Both clinicians have added hypotactic clauses and give the reasons and purpose for the suggested actions. For instance, Wu not only suggests doing exercise, but he also explains from a clinician’s point of view that the purpose for doing exercise is to maintain harmony between human physiology and the atmospheric energy of spring. The same is found in Ni’s translation: he not only asks the reader to take certain actions, but also adds the reasons why these actions need to be taken. The logical connections between these actions are also made explicit.

This clearly illustrates the significant role of medical expertise in tactic choices. However, to be more accurate, there is a need to differentiate the impact of expertise from that of the translators’ mother tongue, as expertise may not necessarily be the only contextual variable that motivates a translator’s tactic choices. In fact, some researchers have argued for the role of a translator’s mother tongue in their stylistic choices, which has led to the establishment of the golden rule or into-mother-tongue principle in the directionality of translation (Venuti 1995/2017; Pavlović 2007; Wang 2011; Xu and Xu 2019). This is directly relevant to this study, as the first language of the clinician translators is Chinese, whereas the non-clinicians, Veith (English) and Unschuld (German), are non-native Chinese speakers. This extra layer of heterogeneity in the translators’ background poses an important question: how important a role does expertise play? In other words, can the observed differences in tactic choices also be attributed to a translator’s mother tongue?

To answer this question, another Li’s translation of Neijing by brought into comparison to test how important a role expertise actually plays (see Table 4):

Table 4

The impact of mother tongue on translators’ tactic choices

In Table 4, Li’s translation is compared with that of non-clinicians, ignoring the variable of expertise (as they are all non-clinicians) and allowing for a comparison to be made under only one variable, that of mother tongue. It shows that mother tongue does not play a significant role in the overall preference pattern of taxis. Indeed, regardless of their mother tongue, Li, Veith, and Unschuld all tend to favour parataxis, with a relatively higher percentage (Li: 53.4%; Veith: 74%; Unschuld: 68.9%) in each translation. This means that mother tongue does not affect the overall preference pattern of tactic choice so much; rather, it is registerial expertise (clinical experience in this case) that plays the central role in the overall preference pattern of tactic choices.

However, if we look at the discrepancy between parataxis and hypotaxis, Li’s translation is clearly much closer to the clinician translations, with 8.8% vs. 0.8%, and is significantly different from the non-clinician translations, with 8.8% vs. 48% and 36.8%. This difference demands further analysis of the differences between Li and the non-clinician translators. Apart from mother tongue, Li is significantly different from Veith and Unschuld in terms of domain-specific knowledge: Li’s education is primarily in the field of linguistics, whereas both Veith and Unschuld are principally educated in the field of medical history. This further suggests that registerial expertise (domain-specific knowledge in this case) plays a significant role in a translator’s tactic choices.

Tactic choices constitute a complicated rhetorical issue. They may also be motivated by stylistic considerations. In hypotaxis, units of information are organized according to their importance, with the most important information receiving primary emphasis in the main clause (Khalil 2011). In parataxis, the information in both clauses receives equal emphasis, creating a certain scope of contextual distance in which various dynamics are allowed (Liu 1983). Paratactic structure in classical Chinese provides enough room for readers’ imagination. For instance, Unschuld indicates that his reproduction of the source text’s format and style is there to help readers “reconstruct the ideas, theories, and practices” of Chinese medicine themselves (Unschuld 2011: 13).[8] This seems to echo Hemingway’s philosophy about his writing style (strong preference for using short and paratactic sentences), known as “the Iceberg Theory”: the dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water, leaving the remaining seven-eighth as room for readers to interpret the crux of the story themselves (Darzikola 2013).

5.3. The role of expertise in logico-semantic choices

Expertise has also been found to play an important role in a translator’s choices of logic-semantic types (See Figure 5).

Figure 5

Choices of logic-semantic types by clinician and non-clinician translators

Figure 5 shows that the type of elaboration is statistically insignificant in all the translations, as indicated by the low percentage of 2.1%, 0%, 0.5%, and 6%, respectively. The discussion will thus only focus on extension and enhancement, which make up the dominant percentage in all the translations.

In Figure 5, a salient variation pattern of logic-semantic types has been found between clinician and non-clinician translators: clinician translators tend to favour enhancement, whereas non-clinicians, extension. This is indicated by the sharp increase in the relative percentage of enhancement, from 25.9% (ST) to 55.5% (Wu) and to 60% (Ni), a much higher percentage compared with 36.7% (Veith) and 35.7% (Unschuld). With regards to extension, the pattern is reversed: compared with clinician translations, non-clinician translations display a higher tendency towards extension, with a percentage of 62.8% and 58.3% respectively. See Example 6 for a further illustration:

6)

|

|

|

|

Translations by clinicians:

α

When a sage treats a patient, ||

× β

precaution is always emphasized…

|

|

|

|

|

|

Translations by non-clinicians:

1

Hence the sages did not treat those who were already ill; ||

+ 2

they instructed those who were not yet ill. |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Example 6 is about ancient Chinese people’s attitude towards health; it suggests that preventing disease was more important than treating it. This example shows clear differences between clinicians and non-clinicians. Clinician translators tend to favour enhancement, while non-clinician translators tend to favour extension. Both clinician translators choose to enhance the meaning by qualifying it with circumstantial elements of time and manner: Wu’s translation is organized in two ranking clauses logically linked by “when,” suggesting time. Ni’s translation is organized in three ranking clauses, with the first one enhanced by the second, suggesting manner, which is in turn enhanced by the third. In Veith’s translation, there are two ranking clauses, the internal logic relation being extension. Unshuld’s translation contains three ranking clauses, the first of which projects the second and third, where the logical relation is extension. This shows that expertise surely affects the choices of specific logical relations.

With regard to the impact of mother tongue, the same method as the one described iin Section 5.2 is applied (see Table 5).

Table 5

The impact of mother tongue on translators’ logico-semantic choices

Table 5 reveals a different preference pattern between translations differentiated by the translator’s mother tongue (the only contextual variable in this case) rather than field of expertise. It shows that Li’s translation tends to favour enhancement (51.7%), whereas Veith and Unschuld tend to favour extension, as indicated by the higher relative percentages of 62.8% and 59.5%, respectively. This means that, apart from the translators’ medical expertise, their mother tongue also plays an impactful role in their choices of logico-semantic relations.

6. Conclusion

This study has investigated the influence of translators’ registerial expertise on their logical choices, focussing on two sets of English translations of Huang Di Nei Jing by clinicians and non-clinicians. By comparing the two groups of translations, it revealed, through several variation patterns, that registerial expertise played a significant role in the translators’ logical choices. Firstly, it shows that translators with and without medical expertise tend to arrange clauses differently. Translators with medical expertise tend to exercise a higher degree of subjective intervention, either by adding important information units or omitting unimportant ones in clause arrangement. Secondly, the two groups of translators tend to produce translations with different degrees of grammatical intricacy: clinician translators tend to produce more grammatically sophisticated translations than non-clinicians do. This might be explained as follows: translators with a higher level of medical expertise tend to have a better capacity for internalizing information and resources (Whyatt 2012; Redelinghuys and Kruger 2015; Whyatt 2018). Moreover, being in the medical field, they might also have more experience judging the value of information. As a result, their translation choices tend to be freer, or bolder, as manifested by the addition of more important information or the omission of some unimportant information found in the source text in their translations, producing more grammatically intricate translations.

With regards to tactic and logic-semantic choices, salient differences have also been discovered between the two groups of translations. However, the explanation is more complicated in this case, involving two major variables at the same time, that is, medical expertise and mother tongue. However, a further round of comparison with Li’s translation reveals that it is medical expertise rather than typological differences (although the latter does have a certain effect) that plays the major role in tactic choices: the translators with medical expertise tend to model the described medical events hypotactically and with more enhancement in making logical relations explicit. This differnce can be largely attributed to the translators’ clinical experience and medical knowledge. Explicitation is one of the “universal” tendencies observed in the process of translating (Zhang, Kruger, et al. 2020). The more medical expertise a translator has, the more able s/he tends to become in providing the explicit reasons and consequences behind certain medical events. Furthermore, a deeper experiential engagement with the medical context may equip a translator with a better sense of the relationships between medical events. They thus tend to have stronger sensitivity to and awareness of institutional demands as well as patients’ concerns about medical reasons and consequences, which perhaps explains why hypotaxis and enhancement are preferred by clinician translators.

Lastly, this research has to be seen as an initial attempt to study the role of registerial expertise in medical translation. Therefore, it is more or less tentative, as it is based on a single case study of translations of Huang Di Nei Jing. Yet, it is also very significant, as it offers clear evidence that has revealed the multifaceted roles of registerial expertise in translators’ logical choices. It is highly encouraged that future research investigate the role of registerial expertise in a large-sized corpus, which may consolidate the results of this study.

Appendices

Appendix

References to the corpus

Wang, Bing (ca. 8th c./1966): The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. (Translated from classical Chinese by Ilza Veith) 2nd trans. ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wang, Bing (ca. 8th c./1995): The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine: a new translation of the Neijing Suwen with commentary. (Translated from classical Chinese by Maoshing Ni) London/Boston: Shambhala.

Wang, Bing (ca. 8th c./ 1997): The Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Internal Medicine. (Translated from classical Chinese by Qi Wu) Beijing: China Science and Technology Press.

Wang, Bing (ca. 8th c./2005): Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine: Plain Question. (Translated from classical Chinese by Zhaoguo Li) Xian: World Publishing Corporation.

Wang, Bing (ca. 8th c./ 2011): Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: An Annotated Translation of Huang Di’s Inner Classic – Basic Questions. (Translated from classical Chinese by Paul Unschuld) Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wang, Bing (ca. 8th c./2015): 黄帝内经素问 (Huang di nei jing su wen) [Inner canon of the Yellow Emperor: basic questions]. Beijing: 中医古籍出版社 (Zhong yi gu ji chu ban she) [Chinese medicine ancient books publishing house].

Acknowledgements

I give my sincere thanks to the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for funding this project. I am also deeply grateful for the practical help provided by several colleagues at Macquarie University, namely A/Prof. David Butt, Dr. Canzhong Wu, and Dr. Florence Chiew, as well as Dr. Pin Wang from Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Without them, I would not have realized the differences that registerial expertise can make in medical translation, and I wouldn’t have become so convinced of the importance of registerial expertise in translator training.

Notes

-

[1]

Olalla-Soler, Christian (2018): The role of expertise and translation strategies when solving translation problems of a cultural nature (unpublished). 24th International Conference of the International Association of Intercultural Communication. Chicago, 5-8 July 2018.

-

[2]

In these discussions, the prototypical grammatical categories are not indeterminate. Indeterminacy is applied to borderline cases.

-

[3]

Veith, Ilza (1966): Preface. In: Bing Wang. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. (Translated from classical Chinese by Ilza Veith) Berkeley: University of California Press, iv-xv.

-

[4]

Matthiessen, Christian (2017): Interview with Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen: On translation studies (Part I). (Interviewed by Bo Wang and Yuanyi Ma) Linguistics and the Human Sciences. 13(1-2):201-217.

-

[5]

Unschuld, Paul (2013): An Interview with Paul Unschuld. (Interviewed by Z’ev Rosenberg) Journal of Chinese Medicine. 103(1):1-8.

-

[6]

Wang, Bing, et al. (ca. 11th c./1978): A Complete Translation of Yellow Emperor’s Classics of Internal Medicine (Nei-jing and Nan-jing). (Translated from classical Chinese by Henry Lu) Vancouver: Academy of Oriental Heritage.

-

[7]

Ni, Maoshing (1995): A Note on the Translation. In: Bing Wang. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine: a new translation of the Neijing Suwen with commentary. (Translated from classical Chinese by Maoshing Ni) London/Boston: Shambhala, xv-xvi.

-

[8]

Unschuld, Paul (2011): Principles of Translation. In: Bing Wang. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: An Annotated Translation of Huang Di’s Inner Classic – Basic Questions. (Translated from classical Chinese by Paul Unschuld) Berkeley: University of California Press, 12-21.

Bibliography

- Amador, Yohanna (2019): The translation task: ITCR students with no expertise in translation. Revista de Lenguas Modernas. 31:43-61.

- Antonini, Rachele and Bucaria, Chiara (2016): Non-professional Interpreting and Translation in the Media. Berlin: Peter Lang.

- Barbe, Katharina (1996): The dichotomy free and literal translation. Meta. 41(3):328-337.

- Baker, Mona (2009): Translation Studies. London/New York: Routledge.

- Baker, Mona (2013): Translation as an alternative space for political action. Social Movement Studies. 12(1):23-47.

- Bisiada, Mario (2013): From hypotaxis to parataxis: an investigation of English-German syntactic convergence in translation. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Manchester: University of Manchester.

- Butt, David and Webster, Jonathan (2017): The logical metafunction in systemic functional linguistics. In: Tom Bartlett and Gerard O’Grady, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Systemic Functional Linguistics. London/New York: Routledge, 96-114.

- Darzikola, Shahla (2013): The Iceberg Principle and the Portrait of Common People in Hemingway’s Works. English Language and Literature Studies. 3(3):8-15.

- Xu, Duo and Xu, Jun (2019): 中国典籍对外传播中的 “译出行为” 及批评探索—兼评《 杨宪益翻译研究》 [“Translating Out” Chinese classics-on Xianyi Yang’s translation study]. Chinese Translators Journal. 5:19.

- Eggins, Suzanne (1994): An Introduction to Systemic Functional Grammar. London: Pinter.

- En, Michael and En, Boka (2019): “Coming out”… as a translator? Expertise, identities and knowledge practices in an LGBTIQ migrant community translation project. Translation Studies. 12(2):213-230.

- Eszenyi, Réka (2016): What Makes a Professional Translator? The Profile of the Modern Translator. In: Ildikó Horvath, ed. The Modern translator and Interpreter. Budapest: Eotvos University Press, 17-27.

- Göpferich, Susanne (2009): Towards a model of translation competence and its acquisition: the longitudinal study TransComp. In: Susanne Göpferich, Arnt Jakobsen, and Inger Mees, eds. Behind the Mind: Methods, Models and Results in Translation Process Research. Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur Press, 11-37.

- Goźdź-Roszkowski, Stanislaw (2016): The role of generic competence and professional expertise in legal translation. The case of English and Polish probate documents. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric. 45(1):51-67.

- Halliday, Michael (2009): Methods—techniques—problems. In: Michael Halliday and Jonathan Webster, eds. Continuum Companion to Systemic Functional Linguistics. New York: Continuum, 59-86.

- Halliday, Michael and Matthiessen, Christian (1999): Construing Experience through Meaning: A Language-Based Approach to Cognition. London: Continuum.

- Halliday, Michael and Matthiessen, Christian (1985/2014): An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 4th ed. London/New York: Routledge.

- Hatim, Basil and Mason, Ian (1990/2014): Discourse and the Translator. London/New York: Routledge.

- Herling, Richard (2000): Operational definitions of expertise and competence. Advances in Developing Human Resources. 2(1):8-21.

- Heritage, John and Raymond, Geoffrey (2005): The terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in talk-in-interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly. 68(1):15-38.

- Holt-Reynold, Diane (1999): Good readers, good teachers? Subject matter expertise as a challenge in learning to teach. Harvard Educational Review. 69(1):29-50.

- House, Juliane (2001): Translation quality assessment: linguistic description versus social evaluation. Meta. 46(2):243-257.

- Huang, Hen-Hsen, Sun, Chuen-Tsai, and Chen, Hsin-His (2010): Classical Chinese Sentence Segmentation. In: Le Sun and Keh-Jiann Chen, eds. Proceedings of CIPS-SIGHAN Joint Conference on Chinese Language Processing. (CLP 2010: CIPS-SIGHAN Joint Conference on Chinese Language Processing, Beijing, 28-29 August 2010). Beijing: Chinese Information Processing Society of China. Consulted on 14 November 2021, https://aclanthology.org/W10-4103.pdf.

- Jia, Yanli (2009): 《内经》误读质疑 [Doubts on the sentence segmentation of Neijing]. Journal of Chinese medicine. 5:476-477.

- Jiang, Xiaohua (2010): Indeterminacy, multivalence and disjointed translation. Target. 22(2):331-346.

- Khalil, Assi (2011): Parataxis, Hypotaxis, Style and Translation. Journal of the College of Basic Education. 16(68):9-18.

- Khoshsaligheh, Masood and Ameri, Saeed (2017): Translator’s Agency and Features of Non-professional Translation of Video Games (A Case Study of Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End). Language Related Research. 8(5):181-204.

- Kies, Daniel (1990): Indeterminacy in sentence structure. Linguistics and Education. 2(3):231-258.

- Liu, David (1983): Parallel structures in the canon of Chinese poetry: The Shih Ching. Poetics Today. 4(4):639-653.

- Liu, Wei and Lin, Wenjuan (2015): A Comparative Study of Terminology between Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine in the Perspectives of Parataxis and Hypotaxis and Hypotaxis in Chinese and English Medical Terms. Medicine and Philosophy. 13:85-88.

- Luo, Shibiao (2005): 说医解字 [Interpreting medicine and the language]. Beijing: Beijing Book Co.

- Maciocia, Giovanni (1989/2015): The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text. 3rd ed. London: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Matthiessen, Christian (2002): Combining clauses into clause complexes. In: Joan Bybee and Michael Noonan, eds. Complex Sentences in Grammar and Discourse: Essays in honour of Sandra A. Thompson. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 235-319.

- Matthiessen, Christian (2009): Meaning in the making: Meaning Potential Emerging from Acts of Meaning. Language Learning. 59(s1):206-229.

- Macarthy, Kathtyn and Goldman, Susan (2019): Constructing interpretive inferences about literary text: The role of domain-specific knowledge. Learning and Instruction. 60:245-251.

- Niederdeppe, Jeffrey (2005): Syntactic indeterminacy, perceived message sensation value-enhancing features, and message processing in the context of anti-tobacco advertisements. Communication Monographs. 72(3):324-344.

- Pavlovic, Nataša (2007): Directionality in collaborative translation processes. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili.

- Popovic, Vesna (2004): Expertise development in product design—strategic and domain-specific knowledge connections. Design Studies. 25(5):527-545.

- Pym, Anthony (2003): Redefining translation competence in an electronic age. In defence of a minimalist approach. Meta. 48(4):481-497.

- Redelinghuys, Karien and Kruger, Haidee (2015): Using the features of translated language to investigate translation expertise: A corpus-based study. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics. 20(3):293-325.

- Rodríguez-Castro, Monica (2018): An integrated curricular design for computer-assisted translation tools: developing technical expertise. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 12(4):355-374.

- Rojo, Ana and Ramos, Marina (2018): The role of expertise in emotion regulation. In: Isabel Lacruz and Riitta Jaaskelainen, eds. Innovation and Expansion in Translation Process Research. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 105-130.

- Russell, Bertrand (1923): Vagueness. The Australasian Journal of Psychology and Philosophy. 1(2):84-92.

- Santos, Diana (1998): The relevance of vagueness for translation: Examples from English to Portuguese. TradTerem. 5(1):71-98.

- Steiner, Erich (1998): A register-based translation evaluation: an advertisement as a case in point. Target. 10(2):291-318.

- Shreve, Gregory (2006): The deliberate practice: translation and expertise. Journal of Translation Studies. 9(1):27-42.

- Shreve, Gregory (2018): Levels of Explanation and Translation Expertise. HERMES. 57:97-108.

- Shreve, Gregory, Angelone, Erik, and Lacruz, Isabel (2018): Are Expertise and Translation Competence the Same? In: Isabel Lacruz and Ritta Jaaskelainen, eds. Innovation and Expansion in Translation Process Research. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 37-54.

- Shreve, Gregory and Lacruz, Isabel (2017): Aspects of a cognitive model of translation. In: John Schwieter and Aline Ferreira, eds. The Handbook of Translation and Cognition. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 127-143.

- Stivers, Tanya (2005): Modified repeats: One method for asserting primary rights from second position. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 38(2):131-158.

- Stivers, Tanya, Mondada, Lorenza, and Steensig, Jacob (2011): Knowledge, morality and affiliation in social interaction. In: Tanya Stivers, Lorenza Mondada, and Jakob Steensig, eds. The Morality of Knowledge in Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 3-24.

- Spranger, Michael and Loetzsch, Martin (2011): Syntactic indeterminacy and semantic ambiguity: A case study for German spatial phrases. In: Luc Steels, ed. Design Patterns in Fluid Construction Grammar. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 265-298.

- Tesseur, Wine (2017): The translation challenges of INGOs: professional and non-professional translation at Amnesty International. Translation Spaces. 6(2):209-229.

- Thompson, Sandra (1987): Subordination and narrative event structure. In: Russells Tomlin, ed. Coherence and Grounding in Discourse. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 435-454.

- Tiselius, Elisabet (2013): Experience and expertise in conference interpreting: an investigation of Swedish conference interpreters. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Bergen: The University of Bergen.

- Tiselius, Elisabet and Hild, Adelina (2017): Expertise and Competence in Translation and Interpreting. In: John Schwieter and Aline Ferreira, eds. The Handbook of Translation and Cognition. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 423-444.

- Trueswell, John, Tanenhaus, Michael, and Garnsey, Susan (1994): Semantic influences on parsing: Use of thematic role information in syntactic ambiguity resolution. Journal of Memory and Language. 33(3):285-318.

- Tse, Yiu-Kay (2010): Parataxis and hypotaxis in the Chinese language. International Journal of Arts & Sciences. 3(16):351-359.

- Venuti, Lawrence (1995/2017): The Translator’s Invisibility. 2nd ed. London/New York: Routledge.

- Wang, Baorong (2011): Translation practices and the issue of directionality in China. Meta. 56(4):896-914.

- Weatherson, Brian (2010): Vagueness as indeterminacy. In: Richard Dietz and Sebastiano Moruzzi, eds. Cuts and Clouds: Vagueness, its Nature and its Logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 77-90.

- Whyatt, Boguslawa (2012): Translation as a Human Skill. From Predisposition to Expertise. Poznaniu: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

- Whyatt, Boguslawa (2018): Testing Indicators of Translation Expertise in an Intralingual Task. HERMES. 57:63-78.

- Williamson, Timothy (2003): Vagueness in reality. In: Michael Loux and Dean Zimmerman, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 690-715.

- Wu, Canzhong (2000): Modelling linguistic resources: a systemic functional approach. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Sydney: Macquarie University.

- Xu, Han, Wang, Hongsu, Zhang, Sanqian, et al. (2019): Sentence segmentation for classical Chinese based on LSTM with radical embedding. Journal of China Post and Telecommunications. 26(2):1-8.

- Ye, Xiao and Dong, Min-hua (2017): A review on different English versions of an ancient classic of Chinese medicine: Huang Di Nei Jing. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 15(1):11-18.

- Yu, Ning (1993): Chinese as a paratactic language. Journal of Second Language Acquisition and Teaching. 1:1-15.

- Zhang, Grace (2015): Elastic Language: How and Why we Stretch our Words. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, Xiaomin, Kruger, Haidee, and Jing, Fang (2020): Explicitation in children’s literature translated from English to Chinese: a corpus-based study of personal pronouns. Perspectives. 28(5):717-736.

List of figures

Figure 1

CLAUSE COMPLEX system, adapted from Halliday and Matthiessen (1985/2014: 438)

Figure 2

An interface for analyzing clause complexes in SysFan

Figure 3

Summary of the translators’ logical choices by SysFan

Figure 4

Tactic and transitivity choices by clinician and non-clinician translators

Figure 5

Choices of logic-semantic types by clinician and non-clinician translators

List of tables

Table 1

Overview of the five translations

Table 2

Overview of the five translators

Table 3

Grammatical intricacy of the translations by clinicians and non-clinicians

Table 4

The impact of mother tongue on translators’ tactic choices

Table 5

The impact of mother tongue on translators’ logico-semantic choices

10.7202/001968ar

10.7202/001968ar